The Biggest News in Diabetes Technology and Drugs: Highlights from ADA 2022

By Andrew BriskinMatthew GarzaJulia KenneyNatalie SainzArvind Sommi

The American Diabetes Association's 82nd Scientific Sessions brought together great minds in diabetes for exciting news and discussions. Check out highlights from the largest conference in diabetes, including automated insulin delivery, Time in Range, extremely promising drugs in development, complications, and diet recommendations.

The American Diabetes Association's 82nd Scientific Sessions brought together great minds in diabetes for exciting news and discussions. Check out highlights from the largest conference in diabetes, including automated insulin delivery, Time in Range, extremely promising drugs in development, complications, and diet recommendations.

Check out our ADA 82nd Scientific Sessions full highlight coverage! This year’s conference covered so many important topics and lots of important research results were presented which highlighted everything from new developments in diabetes technology, medications to prevent diabetes-related complications and reduce A1C, updates on nutrition, and much more.

Click to jump down:

Diabetes Technology

-

Impressive Results From the iLet Bionic Pancreas Pivotal Trial

-

Awareness and access to Time in Range – Opportunities for improvement

-

Severe hypoglycemia persists despite advances in diabetes technology

Diabetes Therapies

-

New Data Builds Case for Tirzepatide as a Weight Loss Game-Changer

-

Medication Options for Treating Chronic Kidney Disease and Hyperkalemia

-

On the Horizon – a Weekly Insulin, Oral Insulin, Smart Insulin, and Biosimilars

Diabetes Complications

Diabetes Stigma

Other Coverage

-

Treating to Fail: Overcoming Therapeutic Inertia in Type 2 Diabetes

-

Hypoglycemia Unawareness: Patient and Clinician Perspectives

-

Preventing Diabetes – 2022 Updates to the ADA Standards of Care

-

Obesity Management as a Primary Treatment Goal for Type 2 Diabetes – It’s Time for a Paradigm Shift

Diabetes Technology

Impressive Results From the iLet Bionic Pancreas Pivotal Trial

The iLet Bionic Pancreas is currently the closest automated insulin delivery system to a fully closed loop system. At ADA's 82nd Scientific Sessions, a panel of experts shared the impressive results from recent the iLet Bionic Pancreas pivotal trial.

Read the full coverage here.

Awareness and access to Time in Range – Opportunities for improvement

At the 2022 ADA Scientific Sessions, diaTribe staff members Julia Kenney and Andrew Briskin presented two posters on the awareness of, and access to, Time in Range (TIR) among healthcare providers (HCPs) in the US. TIR can be a valuable tool in diabetes care. However, the reality is that many HCPs don’t know about the metric and don’t have the resources to effectively use TIR for their patients.

To understand the level of TIR awareness among HCPs, and the barriers they might face in using the metric, diaTribe and dQ&A (a market research company focused on people with diabetes), conducted a survey of 303 HCPs made up of primary care providers, certified diabetes care and education specialists (CDCES), and endocrinologists in the dQ&A US provider panel.

Awareness of TIR

Overall, more CDCES (96%) and endocrinologists (92%) were aware of TIR compared to primary care providers (56%). Primary care providers (PCPs) were also least likely to be familiar with CGM metrics for diabetes care such as Time in Range, Time Above Range, and Time Below Range.

Among the HCPs who were aware of TIR, CDCES were more likely to use TIR to educate (94%) and motivate (77%) their patients and to increase people’s engagement in their own care (82%). Endocrinologists were more likely to use TIR to make treatment decisions (87%). Primary care providers were least likely to use TIR for any of these purposes.

This data indicates that there is a lack of TIR awareness and use among primary care providers. This is particularly concerning given that for many people with diabetes, their primary care provider is their main HCP (or only HCP). Future efforts to increase HCP engagement with TIR should be focused on the need for education and resources among primary care providers.

Click to view our poster on the awareness of TIR.

Access to CGM

The second poster focused on barriers to using TIR. 80% of HCPs identified access to CGM as a critical obstacle to expanded use. Providers said that access to CGM, getting the people that they treat to use it, and the time and infrastructure it takes to download and interpret CGM data are all important issues.

When asked what would improve their care of people with diabetes, HCPs said getting more people on a CGM (39%) and the ability to use TIR data with more people (28%) as the top two solutions. In addition, 41% of HCPs who do not use TIR said that increased access to CGM would convince them to use the metric in their practice.

The data highlights the importance of access to CGM in helping more providers use TIR in their diabetes care. Comprehensive and readily available CGM data would make it easier for HCPs to use TIR with their patients and track their day-to-day glucose variability. The data also shows that TIR non-users are open to using the metric as long as they have the necessary tools and resources.

“We’re excited to present this data, which suggests several potential paths to improve the awareness and use of TIR,” Briskin said. “Increased access to CGM can support the use of TIR by more healthcare providers, potentially improving the lives of millions of people with diabetes.”

Click to view the poster on access to TIR.

Severe hypoglycemia persists despite advances in diabetes technology

Most adults with type 1 diabetes have trouble achieving their glucose managment goals. Diabetes technology has the potential to improve Time in Range (TIR) and reduce diabetes complications. Dr. Jeremy Pettus, Associate Professor Of Clinical medicine, UCSD School of Medicine and author at Taking Control of Your Diabetes (TCOYD), studied whether continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and other diabetes technologies have helped reduce the amount of hypoglycemia in people with type 1 diabetes.

The study evaluated type 1 diabetes management in terms of A1C, impaired awareness of hypoglycemia (IAH), and severe hypoglycemic events (SHEs).

Over 2,000 adults with type 1 diabetes participated in the trial and were split into groups based on whether they used CGM or not. Pettus also considered whether the CGM users combined multiple daily doses of insulin (MDI), a pump, or hybrid closed loop systems with their device.

Despite improvement in glucose management with CGM, 40% of overall participants on CGM did not reach their target A1C. Even worse, 61.3% of non-CGM users did not reach their targets. Comparatively, 35.6% of those using a pump and CGM (or hybrid closed loop systems) did not reach their target A1C.

Additionally, about 30% of participants had IAH, which was similar regardless of CGM usage (including people using a hybrid closed loop system).

Looking at SHEs, the average number was lower among those using CGM, but events still occurred even among people with hybrid closed loop systems. Non-CGM users experience an average of 1.83 SHEs per year, compared to hybrid closed loop users’ average of 0.82. Ultimately, despite using a CGM, a substantial proportion of people with diabetes experience SHEs. However, 34.3% of non-CGM users experienced at least one SHE per year, compared to 18.5% in CGM users.

Although people with diabetes are increasingly adopting diabetes technology, “there exists a substantial unmet need for innovative approaches to improve both glycemic control and decrease severe hypoglycemic events for people with type 1 diabetes,” said Dr. Pettus.

Using Insulin in Type 2 Diabetes – Leveraging Technology

The conversation around innovations in insulin administration is typically dominated by research on type 1 diabetes. Fortunately, the field of research on insulin use for people with type 2 diabetes is growing and so are opportunities for type 2s to leverage new technologies to administer insulin.

Read the full coverage here.

Diet and Exercise with Automated Insulin Delivery

A team of world-renowned experts in diabetes presented updates about automated insulin delivery (AID), focusing on the role of diet and exercise for closed-loop systems.

Read the full coverage here.

Technology education in underserved populations

Devices such as continuous glucose monitors (CGM) and insulin pumps can improve diabetes management, but not everyone has access to these technologies. Studies have shown that whote c children use CGM and insulin pumps far more frequently than Black and Hispanic children. Additionally, a higher A1C was associated with being on public insurance, having lower income, being Hispanic or Black, and not having a CGM.

Through a donation from Insulin for Life, Dr. Anne Peters, director of the University of Southern California Clinical Diabetes Programs, was able to provide CGM to her own patients who did not have access to these devices. Now, she said 80% of her patients use CGM and have seen improved results.

Peters explained that technology access is only part of the story because accessible guidance is also essential. Learning how to use new diabetes technology can be overwhelming and confusing, which may cause people to give up on using devices like a CGM or insulin pump.

The STEPP-UP study showed that when healthcare providers provided people with type 1 diabetes easy-to-read guides (including in Spanish) about how to use diabetes technology, their diabetes knowledge, self-reported health, mental health, and rates of severe hypoglycemia improved.

Dr. Peters also highlighted a new resource called Blue Circle Health which will provide care to under-resourced individuals with type 1 diabetes for free (including people in communities without access to financial resources, quality healthcare and insurance, or who experience additional challenges). Through their holistic care model, Blue Circle Health will offer peer coaching, insurance support, medications and supplies, and other diabetes management services.

“If you give people the right tools and the right resources,” Peters said, “you can improve their outcomes.”

Getting CGM Data Into Electronic Health Records

An electronic health record (EHR) is a way for healthcare providers to digitally upload, access and analyze their patient’s data. This record typically includes medical history, medications, lab reports from blood work, and other essential information about a person’s health.

This data in the EHR allows doctors to more easily optimize care so that they are providing as personalized care as possible. The EHR also enables providers to assess population health.

Although 48% of people with type 1 diabetes rely on a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), this data is not yet integrated into the EHR. This information gap can complicate the data review process for doctors as they have to log into several different websites and platforms and piece together all the information in the relatively short time they have with their patient.

“We’ve always thought diabetes is complicated enough,” said Dr. Richard Bergenstal MD, executive director of the International Diabetes Center (IDC). “The data shouldn’t be the complicated part.”

Bergenstal has worked on a way to integrate CGM data into the EMR at the International Diabetes Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota. “Easy access allows more time to review and discuss the data,” he said.

Bergenstal also reviewed the evolving impact of CGM data:

-

Standardize CGM data

-

Organize CGM data into a useable report

-

Integrate CGM data Directly into the EHR

-

-

Analyze a CGM report in a systematic way

-

Act on the CGM report to optimize glucose

Dr. Juan Espinoza an Informatics Physician at the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles has also been working on integrating CGM and other devices into the EHR. A group of stakeholders has started working on iCoDE, an effort to help integrate CGM data into the EHR. iCoDE will meet throughout 2022 and beyond to create a set of data standards and guidelines for this purpose.

“We don’t do this because it’s fun,” said Espinoza, “we do this to take better care of our patients.”

Diabetes Therapies

New Data Builds Case for Tirzepatide as a Weight Loss Game-Changer

Dr. Ania Jastreboff, of the Yale University School of Medicine, and colleagues presented new data at the ADA 82nd Scientific Sessions in New Orleans, Louisiana, on the SURMOUNT-1 trial, which investigated the effectiveness of tirzepatide, a drug recently approved as Mounjaro by the FDA for treating type 2 diabetes, for the treatment of obesity.

Read the full coverage here.

Medication Options for Treating Chronic Kidney Disease and Hyperkalemia

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a serious complication that affects approximately 40% of people with type 2 diabetes. According to Dr. Csaba P. Kovesdy, professor of medicine and chief of nephrology (kidney specialist) at University of Tennessee Health Science Center, chronic kidney disease (CKD) can shorten life span by 16 years for people with diabetes.

Kovesdy reviewed two major clinical trials: FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD. Both of these trials investigated the effectiveness of Kerendia (finerenone), a diabetes medication recently approved by the FDA. He said that although these trial results held promise for using finerenone to treat CKD, “there is large untapped potential.” Current research is investigating if combining both finerenone and an SGLT-2 inhibitor could be even more effective.

This overview was followed by a presentation on hyperkalemia, which is when there is higher than normal potassium levels in the blood. Dr. Bill Palmer, a professor at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, presented a case study of someone with hyperkalemia and the steps he would recommend for treatment.

“You have to be nuanced when you discuss diet with patients since you might withhold foods that have cardiac benefits,” said Palmer, noting that it may not be wise to lower the amount of potassium enriched foods, such as fruits and vegetables, in one’s diet. He also discussed types of medications, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), which are routinely used to treat high blood pressure and diabetic kidney disease.

Unfortunately, these two classes of medications can lead to hyperkalemia. Healthcare professionals are faced with the challenge, “a Catch-22,” as he phrased it, of prescribing drugs that slow the progression of CKD but can cause hyperkalemia, or avoid hyperkalemia while risking a faster progression of CKD.

In response, Dr. Palmer said that he would review the situation and see if he could discontinue or adjust any medications, use diuretics (medications that promote urine production and therefore reduce potassium levels), and SGLT-2 inhibitors in combination with or in place of ACE inhibitors or ARBs to decrease the frequency of hyperkalemia.

Medications You Should Take if You Are at Risk for Stroke

In an insightful presentation on the first day of the American Diabetes Association’s 82nd Scientific Sessions, Dr. Liana Billings, vice chair of research and education for the Department of Medicine at NorthShore University HealthSystem, made a powerful case for why GLP-1 receptor agonists, and not SGLT-2 inhibitors, should be the go-to therapy for treating and preventing ischemic strokes in people with diabetes.

Ischemic strokes, which make up roughly 88% of all strokes, occur when you have a blood clot in a blood vessel in the brain or when one of these vessels narrows. When this happens, blood flow cannot get to the brain and your cells start to die.

Recent data on strokes is alarming. Around 30% of people who have a stroke also have diabetes and people with diabetes are up to three times more likely to have an ischemic stroke. Billings explained that having a stroke was shown to be one of the most feared conditions among people with diabetes.

Billings grounded her argument in the data. Meta-analyses of studies conducted over the past several years (which look at data from a number of different studies of the same subject to identify trends) show that GLP-1 receptor agonists can lower the risk of stroke up to 17% compared to a placebo. The most recent meta-analysis that Billings presented included eight different GLP-1 receptor agonist cardiovascular outcome trials (CVOT). In comparison, meta-analyses of SGLT-2 inhibitor CVOT trials showed that these medications may not have the same level of protection.

Interestingly, researchers are not yet positive why this is the case. Billings explained that some of the potential explanations include the fact that GLP-1 receptor agonists reduce A1C drastically, affect blood pressure, and may potentially protect the nerves and blood vessels in the brain.

Though GLP-1 receptor agonists have documented advantages when it comes to protection against ischemic strokes, Billings highlighted that GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT-2 inhibitors are complementary and interconnected. They both have positive benefits and protective effects for people with diabetes.

Her suggestion to all healthcare providers is to adopt a mindset that views these medications not as an “either/or” relationship but instead as an “and” relationship. There is potential for these medications to work together to help people with diabetes avoid harmful complications.

She also stressed the need for more research on these glucose-lowering medications and their cardioprotective benefits as well as educating other healthcare providers and specialists who may not know of the benefits of these medications.

Semaglutide 2.4mg (Wegovy) Could Prevent Type 2 Diabetes

New research presented by Dr. Timothy Garvey, professor of medicine in the Department of Nutrition Sciences at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and others suggest that a 2.4mg dose of semaglutide, currently sold as Wegovy and indicated only for people with obesity, reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes for people with obesity.

Garvey, the lead investigator who presented the findings along with Dr. Jason Brett, executive director at Novo Nordisk, said, “Obesity is one of the main drivers associated with type 2 diabetes.”

This study, which used a model to predict risk for type 2 diabetes, focused on how treatment with semaglutide, a glucose-lowering and anti-obesity medication, affected the risk for type 2 diabetes. The results indicated an approximate reduction of 60% in the 10-year risk of developing type 2 diabetes after treatment with once-weekly semaglutide for 68 weeks.

Importantly, they found a significant risk reduction for people in the study who had prediabetes and were at risk for type 2 diabetes.

Garvey specified that the model incorporates “quantitative data readily available to clinicians and is highly predictive of who is going to get type 2 diabetes.” This data includes sex, age, race, BMI, blood pressure, blood glucose, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol.

|

Absolute 10-year T2D risk scores in all participants |

||

|

Week 0 |

Week 68 |

|

|

Semaglutide 2.4mg |

18.2 |

7.5 |

|

Placebo |

17.8 |

15.6 |

Garvey said that although extensive data exists on the weight loss potential from semaglutide 2.4mg, “there has not been a study done to look at diabetes prevention [until now].”

When comparing participants with and without prediabetes, both experienced reductions in risk scores for type 2 diabetes but those with prediabetes had a higher risk, so they had a greater overall reduction in risk based on the model.

“Two-thirds of America are overweight or have obesity,” Garvey said. “With a tool like this, you could identify those most at risk for type 2 diabetes and bring more aggressive therapy to them.”

On the Horizon – a Weekly Insulin, Oral Insulin, Smart Insulin, and Biosimilars

Insulin has come a long way since its discovery over 100 years ago. Learn what new insulin options may be on the horizon that could revolutionize the way diabetes is managed.

Read the full coverage here.

Diabetes Complications

Liver Disease in Diabetes – An Overlooked Complication

NAFLD and NASH are two types of liver disease that affect many people with diabetes, however, they are only just now getting the attention they deserve and unfortunately there are only limited treatment options currently available. Hear what experts have to say about the prevention and management of these conditions.

Read the full coverage here.

How Diabetes Impacts Cognition

Among diabetes-related complications, sometimes overlooked is the very real effect diabetes can have on the brain and cognition. Researchers and healthcare providers at this year’s ADA Scientific Sessions discussed how diabetes can impact cognition in children and adults.

Cognition in children

Many people with type 1 diabetes are diagnosed in childhood, and rates of type 2 diabetes in children are increasing. Because childhood is a period of rapid brain growth and development, diabetes can impact the process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses – cognition and the way a child’s brain functions.

Dr. Lara Foland-Ross, a neuroscientist at Stanford University, presented research demonstrating differences in brain structure and IQ in children with type 1 diabetes, especially those with greater exposure to hyperglycemia. Foland-Ross demonstrated that even short-term improvements in glucose variability can improve brain structure and cognitive outcomes in children with type 1 diabetes.

According to Dr. Allison Shapiro, assistant professor at the University of Colorado’s Anschutz Medical Campus, children with type 2 diabetes have worse mental processing speed and working memory (short-term memory that deals with language processing and holding information temporarily) than children without diabetes. Children with type 2 also had worse overall fluid cognition (capacity to process information and act to solve new problems) than children with type 1 diabetes.

She said more research is needed on this topic to understand what exactly is causing this cognitive decline.

Adults with diabetes

Complications in the brain can extend into adulthood and become more severe. Diabetes can lead to dementia in adults, which is an “impaired ability to to remember, think, or make decisions that interferes with everyday activities,” according to the CDC. The most common form of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, which is characterized by a buildup of abnormal proteins in and around brain cells.

Dr. Naomi Chaytor, associate professor at Washington State University’s College of Medicine, presented research showing that dementia in people with type 1 diabetes is associated with episodes of severe hypoglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). In this study, combined risk factors of A1C, systolic blood pressure, and severe hypoglycemia equated to 9.4 years of premature cognitive aging. In contrast, people with stable glucose levels and lower risk factors for cognitive decline have minimal levels of decline as they age.

Adults with type 2 diabetes are also at a higher risk for dementia, specifically Alzheimer’s disease. In a study of 1,700 Latinos aged 60-101, 43% of the risk for dementia was attributed to type 2 diabetes or stroke. It is possible that type 2 diabetes medicines such as metformin could be used in the future for cognitive decline in type 2 populations.

While dementia is a health complication on its own, it makes diabetes management extremely difficult due to declines in memory and general physical and cognitive function. Though we don’t have much information yet on potential treatment or mitigation strategies, experts recommend avoiding hypoglycemia and maintaining a Time in Range greater than 70% as key strategies to maintain cognitive health.

The Forgotten Complications – What You Should Know

Heart disease, chronic kidney disease, and nerve damage tend to dominate the conversation around diabetes-related complications. However, there are several overlooked complications relating to bone health, the brain, and the skin. Experts discuss these complications and more at the 82nd ADA scientific sessions.

Read the full coverage here.

Let’s Talk about Sex and Diabetes

Though certain sexual disorders are well-understood in men with diabetes, we know a lot less about the prevalence, impact, and management of sexual dysfunction in women with diabetes. At the ADA Scientific Sessions, Dr. Sharon Parish gave a broad overview of what we do know about this topic.

Read the full coverage here.

Diabetes Stigma

It’s Time to Address Diabetes Stigma

Diabetes stigma is a huge public health problem that has been shown to lead to worse health outcomes. At the ADA 82nd Scientific Sessions, four leading experts in this field discuss the prevalence of stigma, interventions to address this issue, and what work still needs to be done.

Read the full coverage here.

Diabetes stigma in adolescents and young adults

Stigma continues to be a huge driver of stress and worse health outcomes among people with diabetes. Angela D. Liese, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of South Carolina, discussed how diabetes stigma can have particularly dramatic effects in adolescents and young adults with diabetes.

Diabetes stigma, as defined by Liese, refers to the experiences of exclusion, rejection, or blame that people unfairly experience due to social judgment about their condition.

Adolescents and young adults with diabetes are especially vulnerable to stigma given the importance of personal identity, peer relationships, and becoming independent during this stage of life. Additionally, young adults tend to have trouble with glucose management when in the early stages of taking ownership of their own care after leaving home.

Liese discussed results from the SEARCH study, which looked at the association between diabetes stigma and glucose management, treatment regimen, and complications in young adults with diabetes. The study was racially and ethnically diverse, and 78% of participants had type 1 diabetes.

The study found that diabetes stigma was associated with higher A1C, higher risk for severe hypoglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in people with type 1, and a higher risk for retinopathy (eye disease) and kidney disease caused by diabetes.

Because of these associations, Liese said she was optimistic that addressing stigma may lead to improved long-term outcomes. “In order to combat diabetes stigma,” she said, “public health education should focus on increasing awareness of diabetes, and what it looks like to live with this condition.”

Using Person-First Language in Scientific Research – Are We Succeeding?

At the ADA 82nd Scientific Sessions, Matthew Garza, who helps lead the Stigma Program at The diaTribe Foundation, contributed to a powerful poster exhibit on the use of person-first language in scientific- and academic-research articles, in conjunction with a team of language and stigma experts and Gelesis, a biotechnology company focused on treating obesity and other gut and stomach-related chronic diseases.

Person-first language avoids labeling people with their disease and recognizes that there is more to a person than their diabetes. It means using terms like “person or people with diabetes” instead of the all too common practice of using “diabetic” or “diabetics”.

Research has shown that when identity-first language is used over person-first language, it can lead to feelings of low self-esteem and isolation which contribute to worse diabetes outcomes.

Despite the fact that many professional organizations endorse the use of person-first language in communications involving people with diabetes and obesity, condition-first language is still widely used. This contributes to stigma associated with both diabetes and obesity.

To better understand the extent to which academic and scientific articles focusing on diabetes or obesity use person-first language, the research team identified a long list of terms associated with person-first language and then conducted a search of all the scholarly articles published between 2011 and 2020 to see which ones use each type of language to describe people with diabetes and obesity.

The results were quite shocking, and showed that while small improvements have been made, the adoption of person-first language has slowed substantially in articles about diabetes and has made almost no progress in articles about obesity.

In over 56,000 articles for diabetes during this time frame, only 42.8% used person-first language. In over 45,000 articles on obesity, 0.5% used person-first language.

When broken down further there are some key trends that come to light. Diabetes articles were more likely to use person-first language if they were published in a diabetes-specific journal, while obesity articles were more likely to use person-first language if they were published in a US-based journal.

If that journal had a language policy emphasizing person-first language, or if the article published more recently, both obesity and diabetes articles were more likely to use person-first language.

The way people talk about, and directly to, people with diabetes, especially in healthcare and media settings, influences the language people in the diabetes community use to refer to themselves.

Choosing to use person-first language in scientific publications can set an example for the way healthcare professionals communicate about and to people with diabetes. This can, in turn, create a large-scale shift, pushing us towards communication that always puts emphasis on the individual.

You can see the full poster here.

Other Coverage

Treating to Fail: Overcoming Therapeutic Inertia in Type 2 Diabetes

Studies show that for people with type 2 diabetes, starting treatment more intensely right after diagnosis can make a monumental difference in preventing diabetes-related complications, resulting in better long term outcomes. However, people with diabetes and their providers are often reluctant to be more aggressive when prescribing additional medications to treat diabetes. Instead, healthcare providers wait until the current treatment fails before moving to the next line of treatment.

This is known as the “treat to fail” approach to diabetes management, or therapeutic inertia, and results in worse outcomes for people with type 2 diabetes and a larger burden on the overall healthcare system. Christine Beebe, a registered dietician and consultant specializing in diabetes patient and health professional services, discussed the reasons why therapeutic inertia exists.

According to Beebe, a lack of communication and trust between people and providers, as well as cost and access to the latest medications, prevent many people from starting on more than one medicine right at diagnosis. Additionally, when healthcare providers failed to set and use target glucose goals at diagnosis, they were less likely to advance treatment for the people in their care.

Several new approaches to diabetes care may help address these issues and preserve the health of people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. According to a study identifying strategies to overcome clinical inertia, the most effective strategies involved empowering non-physicians, (such as pharmacists, nurses, and certified diabetes care and education specialists (CDCES)) to independently make treatment adjustments. In fact, the study showed that involvement from pharmacists and educators actually led to significant reductions in A1C.

Consulting a CDCES and seeking out virtual coaching as early as possible can complement care from your physician and potentially help you avoid diabetes-related complications down the road.

“In order to have good long-term outcomes for the patient, primary care provider, and overall healthcare system, we need to get to good glycemic control within the first six months to a year after diagnosis,” said Beebe. “This achieves a legacy effect, establishing metabolic memory for good glycemic control early on.”

What to Eat, When to Eat – New Nutrition Learnings

When trying to manage your diabetes, figuring out what to eat and when to eat can be difficult. The most important thing to understand is that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to diabetes nutrition. Everyone has different nutritional needs and food tastes. Alison Evert, a certified diabetes care and education specialist and registered dietitian nutritionist with the University of Washington, outlined the following recommendations on ways to approach meals, snacks, and weight loss.

-

With a diabetes care team, coordinate your eating plan with your diabetes medication plan. For example, have a clear understanding of when and how to bolus (deliver mealtime insulin) before snacks and meals.

-

There is no general guideline for how many carbohydrates, proteins, and fats to eat. Your dietary targets should be determined with your healthcare team based on your individual needs.

-

Continuous glucose monitoring can be a valuable tool to understand how different foods impact your blood sugar.

-

Eating breakfast regularly may help improve your postprandial (after meal) blood sugar later in the day as long as you are not increasing your daily intake of calories.

-

Structured, low calorie diets, mediterranean-style diets, and low carbohydrate diets (also known as ketogenic diets) can be used to achieve weight loss goals.

Even though there are no officially agreed-upon nutrition guidelines, diaTribe has several guiding principles listed on our website: "What to Eat with Diabetes."

Maureen Chomko, a certified diabetes care and education specialist and registered dietitian with Neighborcare health, discussed artificial sweeteners and ketogenic diets. While many people with diabetes substitute sugar for artificial sweeteners in drinks, according to the American Diabetes Association’s Standards of Care, “there is not enough evidence to determine whether sugar substitute use definitively leads to long-term reduction in body weight or cardiometabolic risk factors.”

Artificial sweeteners may even increase your risk for obesity, type 2 diabetes, and related complications. When possible, Chomko recommends choosing low- or no-sugar drink options such as water and tea.

Ketogenic diets are high in fat and low in carbohydrates and have been shown to increase weight loss, reduce A1C, and reduce insulin doses and other medication requirements. Chomko explained that ketogenic diets may be a safe diabetes management and weight loss strategy in the short term (up to 6 months), but data on long term safety and outcomes is scarce.

If you have type 1 diabetes, a ketogenic diet may increase blood ketones which may increase the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). If you are considering a ketogenic diet, consult your healthcare provider, especially if you are on insulin, a sulfonylurea, an SGLT-2 inhibitor, a diuretic, or have chronic kidney disease.

Hypoglycemia Unawareness: Patient and Clinician Perspectives

For many people with diabetes, managing hypoglycemia can be a significant challenge. It’s even more challenging for people with a condition called hypoglycemia unawareness, which happens when the person does not recognize when they have low blood sugar. People with hypoglycemia unawareness often do not promptly treat their low blood sugar, which can worsen an already dangerous condition.

As a person who has lived with diabetes for 16 years, Anna Kasper, a registered nurse and diabetes education specialist at Mayo Clinic, is familiar with the feelings that come with hypoglycemia. Kasper recounted her personal stories of experiencing impaired awareness of hypoglycemia.

“Experiencing hypoglycemia is complex,” explained Kasper. It comes with several different emotions that include:

-

Embarrassment - Due to stigma and unintentional behavior during the hypoglycemic episode

-

Defeat – Continued problems in spite of constant work to avoid hypoglycemia

-

Anxiety - Which can mirror hypoglycemia or exacerbate it

-

Isolation – Avoiding certain activities or situations, feeling alone or misunderstood

-

Exhaustion – Due to the physically, emotionally, and mentally taxing toll of hypoglycemia

To help manage these emotions, Kasper provided a recommendations for healthcare providers and loved ones caring for people with diabetes:

-

Empathy: Verbal and physical responses are extremely powerful. Be mindful.

-

Empowerment: Encourage education and co-create action plans

-

Lifelong support: Foster mental flexibility and family education

-

Therapy: Normalize professional help from a therapist

Continuous glucose monitors (CGM) can also be helpful in preventing hypoglycemia, but there are limitations in terms of ease of use and access to the device. Kasper shared her perspective on ways that healthcare providers can improve CGM use, suggesting several steps including:

-

Advocate for people to increase affordability and accessibility, and help with appeal insurance denials. “Sometimes even the most affordable CGM on the market can still be too much out of pocket for some patients,” said Kasper.

-

Become familiar with international standards on CGM & A1C: Many people are not aware.

-

Review expectations about blood glucose and CGM values.

-

Understand emotional responses to colors, trend arrows, alerts, alarms, numbers, and percentages. Be mindful of these responses.

From the healthcare provider perspective, Dr. Pratik Choudhary of King’s College London stressed that clinicians need to use metrics to assess hypoglycemia while also recognizing the pros and cons of those metrics.

“A1C is a poor metric to assess the risk of hypoglycemia because it does not help quantify the risk of hypoglycemia,” Choudhary said. Better metrics to measure hypoglycemia including TIR from CGM may facilitate better care and more rapid treatment of severe lows.

“We need to understand the emotional and physiological impact of those events,” Choudhary said. He concluded his presentation by recommending that healthcare providers develop personalized treatment plans based on an understanding of the needs of each person.

A Transformative Approach to the Prevention and Control of Diabetes in the U.S – The National Clinical Care Commission 2022 Report to Congress

“Diabetes is not simply a health condition that requires medical care but also is a societal problem that requires a trans-sectoral, all-government approach to prevention and treatment,” said Dr. William Herman of the University of Michigan.

To that end, the National Clinical Care Commission (NCCC) was started in 2018 by the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services to evaluate and make recommendations regarding improvements to the coordination and leveraging of programs, such as within the department of health and human services. “

Herman started the session by overviewing the main purpose and foundational recommendations of the NCCC. He highlighted that diabetes cannot simply be viewed as a medical problem, but must be addressed as a societal problem. US federal policies and programs should ensure that people with diabetes have access to comprehensive, high-quality, and affordable health care.

Herman also said that health equity should be considered in every new federal policy or program that impacts people with diabetes. This could help eliminate unintended, adverse impacts that these policies and programs may have on health disparities.

Dr. Dean Shillinger of the University of California, San Francisco provided context on the social determinants of health for people with diabetes and the implications of certain government policies. One major focal point of his presentation was food insecurity.

Although federal programs like the USDA Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, also known as food stamps) have gone a long way in improving nutrition, Schillinger noted that over $4 billion of the SNAP budget is used to purchase sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB). This is in comparison to the ~$600 million used for federal chronic disease prevention and control.

He added that about half of Americans, both children and adults, do not drink tap water, a number which is even higher for certain racial minorities, such as African Americans. This is due to either the real or perceived threat that tap water is unsafe. He said we should provide clean water instead of sugar-sweetened beverages.

The NCCC recommends that all relevant federal agencies promote the consumption of water and reduce the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages in the United States.

“The Treasury Department should impose an excise tax on SSBs to cause at least a 10% increase in their shelf price,” Shillinger proposed, “and the revenues should be invested in diabetes prevention and control in those communities that bear a disproportionate burden of type 2 diabetes.

Preventing Diabetes – 2022 Updates to the ADA Standards of Care

Over 11% of the US population has diabetes and over 30% has prediabetes. Projections on the prevalence of diabetes estimate that without effective diabetes prevention interventions, these numbers will continue to grow.

Dr. Jane Reusch, professor of endocrinology at the University of Colorado’s Anschutz Medical Campus, said that right now “we are not preventing diabetes in the US.” She said that if we, as a society, began doing everything possible to prevent the onset of diabetes, the effort would be “worth it.”

Early-onset diabetes can shorten a person’s lifespan, and any work to prevent or delay the onset of diabetes can lead to improved health outcomes down the line, Reusch said. Along these lines, a team of diabetes experts, of which Reusch was a member, and clinicians worked to bolster diabetes prevention recommendations in ADA’s 2022 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes (2022 SOC).

Social determinants of health

“When we’re thinking about the prevention of diabetes, we want to be comprehensive,” Reusch said. This means providing care that addresses the social determinants of health, in addition to the physical health of those at risk for diabetes.

To encourage providers to have a more holistic approach to diabetes care, the 2022 SOC recommends that health care providers:

-

Assess food insecurity, housing insecurity/homelessness, financial barriers, and social capital/social community support to inform treatment decisions, with referral to appropriate local community resources.

-

Provide people with self-management support from lay health coaches, navigators, or community health workers when available.

-

Screen for prediabetes and treat any modifiable risk factors (such as smoking, high blood pressure, or physical inactivity) for cardiovascular disease.

Individualizing care

Dr. Vanita Aroda, an endocrinologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, discussed the importance of individualizing care for those at risk for type 2 diabetes. The 2022 SOC includes the following recommendation focused on a person’s risk factors and individual health needs:

-

In adults with overweight/obesity at high risk of type 2 diabetes, care goals should include weight loss or prevention of weight gain, minimizing progression of hyperglycemia, and attention to cardiovascular risk and associated comorbidities.

Reusch explained that other components of individualizing diabetes care include a comprehensive assessment of risk factors for diabetes, diabetes education, support for behavioral change, a comprehensive prevention of complication progression, and employing evidence-based therapies when necessary.

Weight loss medications and nutrition

Dr. Scott Kahan, director of the National Center for Weight & Wellness, said that “weight loss largely drives diabetes risk,” adding that just one kilogram of weight loss can lead to a 16% reduction in a person’s risk for diabetes. To address weight loss, the 2022 SOC recommend the following lifestyle and therapy interventions:

-

Refer adults with overweight/obesity at high risk of type 2 diabetes, as typified by the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), to an intensive lifestyle behavior change program consistent with the DPP to achieve and maintain 7% loss of initial body weight, and increase moderate-intensity physical activity (such as brisk walking) to at least 150 min/ week.”

-

Metformin therapy for prevention of type 2 diabetes should be considered in adults with prediabetes, as typified by the Diabetes Prevention Program, especially those aged 25-59 years with BMI >35kg/m2, higher fasting plasma glucose (>110 mg/dL), and higher A1C (>6.0%), and in women with prior gestational diabetes mellitus.”

The Diabetes Prevention Program’s lifestyle interventions such as nutrition counseling, exercise, and diabetes care education, reduced the risk of diabetes onset by 58% in those with prediabetes.

Kahan said that medications that address weight loss “have been shown to decrease the incidence of diabetes,” though none have been approved for diabetes prevention.

Supporting Teens with Type 2 Diabetes

While type 1 diabetes can be diagnosed in very young children, type 2 diabetes in youth is often diagnosed around the time of puberty – a period of significant physical and mental transitions for young people. Because of this, learning to manage diabetes as a teenager can be difficult. Both healthcare providers and family members should work together to support their mental and emotional well-being, in addition to their physical diabetes health.

In a presentation on addressing psychosocial outcomes in youth with type 2 diabetes, Dr. Lauren Gulley, a clinical psychologist at Colorado State University, described the mental health barriers that many young people with type 2 experience.

Because 85% of youth with type 2 have a high BMI (≥85th percentile), they are at a high risk for weight stigma. Experiencing weight stigma can lead to feelings of shame, low self-esteem, and lifestyle behaviors that could further increase weight.

To address this, Gulley recommends providers and parents of youth with type 2 diabetes do the following:

-

Focus on sustainable diabetes self-management strategies that youth have control over.

-

Ask youth about their experience coping with major diabetes-related stressors.

-

Consider the impact of family support and conflict, especially from family members who may also have type 2 diabetes.

-

Normalize and validate uncomfortable experiences that come with type 2 diabetes.

-

Ask permission to discuss weight. Ask for preferred words or language to use.

Youth with type 2 diabetes are also at high risk for exposure to racism, discrimination, and violence, since about 80% of them come from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds. Gulley explained that young people with type 2 diabetes are also likely to come from low-income, single-parent households, and experience major life stressors.

To address this, Gulley recommends that healthcare providers and caregivers acknowledge the role of the environment on facilitators and barriers to self-management of type 2 diabetes.

Youth with type 2 diabetes are also at a high risk for depression, self harm, and eating disorders. About 20% of youth with type 2 experience depression and 25% report behaviors associated with disordered eating.

Gulley recommends providers, with the support of families:

-

Add screening questions in healthcare visits to assess mental health outcomes and disordered eating risks.

-

Normalize and validate mental health outcomes.

-

Make the connection between teens’ mental health issues and teen’s management of weight and type 2 diabetes.

-

Refer teens to a qualified therapist, mental health treatment or crisis services when necessary.

Look here for ADA’s new “Safe at School” diabetes medical management plan to help schools better support their youth with diabetes.

Weight Loss Through Time Restricted Eating

Dr. Krista Varady of the University of Illinois College of Medicine led a research study on time restricted eating (TRE) where participants only had an 8-hour eating period, from 10 am to 6 pm. During the remaining 16 hours of the day, participants could only drink water and zero-calorie drinks.

She found that this 8-hour TRE reduced energy intake by 350 kcal per day, resulting in a weight loss of 2.6% over 12 weeks.

Varady then wanted to see if the outcomes might change with a 6-hour eating period, 1 pm to 7 pm or even a 4-hour eating period, 3 pm to 7 pm. In both of these groups, participants lost about 3.2% of their weight. Participants in both 4-hour and 6-hour reduced their energy intake by about 550 kcal per day.

Some researchers questioned if participants would gravitate toward energy-dense, high-fat foods during these shorter eating windows, but interestingly, Varady’s team found that the proportion of these foods remained constant even after switching to a shorter eating window.

Varady concluded with some practical considerations when translating her research into clinical practice. First, she noted that while the 6-hour eating period may be feasible for a few months, the 4-hour eating period is not sustainable over the long term for most people. The 8-hour eating window will be the easiest for most people to follow. Additionally, she noted that people are much more likely to adhere to the eating schedule if they are allowed to eat dinner, either by themselves or when they are with friends and family.

Those just starting TRE may experience an adjustment period: “You feel hungry and lethargic for the first 10 days, but then most people feel great on fasting days,” Varady said, adding a disclaimer that certain populations should not fast, such as children under 12, adults over 70, pregnant women, and people with eating disorders.

Obesity Management as a Primary Treatment Goal for Type 2 Diabetes – It’s Time for a Paradigm Shift

Obesity has been established as one of the key risk factors for type 2 diabetes. This has led to growing interest in obesity management to supplement glycemic management as a treatment goal for type 2 diabetes. Ricardo Cohen, a surgeon from the Oswaldo Cruz German Hospital, and Ivania Rizo, an endocrinologist from Boston Medical Center, presented current therapeutic options for obesity management at the American Diabetes Association 82nd annual Scientific Sessions.

As a surgeon, Cruz strongly supports bariatric surgery. He presented the results of a study showing that 73% of participants who had a form of bariatric surgery reduced their hypertension (high blood pressure) medications by 30% while maintaining a blood pressure of less than 140/90 mmHg. He followed this with results from another study that showed there was al 41% decrease in mortality for participants who had bariatric surgery versus those who did not have the surgery.

When looking specifically at the participants who had pre-existing type 2 diabetes, there was an even greater (around 60%) reduction in mortality. He supported this information with safety data that shows only a 3.4% composite complications rate for people undergoing a type of bariatric surgery called RYGB.

In a meta analysis of all the current studies investigating type 2 diabetes remission after baritric surgery, there was a 72% remission rate for people with BMIs under 35 and a 71% remission rate for people with BMIs over 35.

Overall, bariatric surgery leads to long term significant weight loss, type 2 diabetes remission, improved kidney health, and a decrease in heart disease risk factors. He concluded by suggesting that lifestyle changes should be tried first, and then medications should be provided to combat obesity. If the person does not respond well to either, then surgery is a good option and it might be ideal if the person took anti-obesity medications after the surgery for a combination therapy.

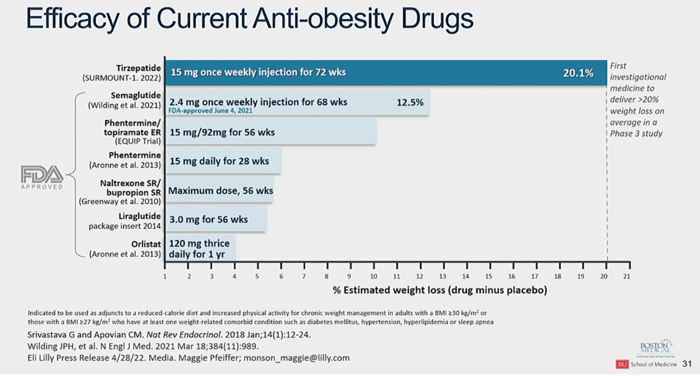

Rizo followed up with a presentation on the treatment of both diabetes and obesity. In the figure below, she overviewed the efficacy of current anti-obesity drugs. She highlighted that the addition of Semaglutide (a GLP-1 receptor agonist) and Tirzepatide have revolutionized obesity management with their impressive weight reduction results. However, it should be noted that tirzepatide is not yet approved in the US by the FDA for the treatment of weight loss, specifically.

She went into detail how researchers currently believe Tirzepatide works in the body as a dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist. Tirzepatide is attracted to, and binds with, the same GIP receptors in your cells as the GIP hormone that your body naturally makes. Additionally it is also attracted to, and binds with, the same GLP-1 receptors in your cells as your body’s natural GLP-1 hormone, however, this connection is about five times weaker (than the natural hormone). GLP-1 is the main hormone in your that results in a decrease in blood sugar and reduces appetite.

This chart compares the average estimated percent weight loss for tirzepatide along with current FDA-approved weight-loss medications. Tirzepatide far surpasses the weight loss results shown by currently available medications.

Understanding How Diabetes Impacts LGBTQ+ People

It may not seem like there’s a connection between having diabetes and being a member of the LGBTQ community. However, the little research we have shows that not only are LGBTQ individuals at an increased risk for obesity and diabetes, they also face challenges within the healthcare system that may make diabetes management more difficult.

Dr. Nicole VanKim, assistant professor at University of Massachusetts Amherst, and Dr. Carl Streed, research lead for the Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery at Boston Medical Center and assistant professor at Boston University School of Medicine, described some of the data showing the prevalence of diabetes and obesity in the LGBTQ population.

Both speakers cautioned that this data has severe limitations.

-

In one study, gay and bisexual men were more likely to report a lifetime diagnosis of diabetes compared to heterosexual men. No difference was observed between sexualities in women.

-

In another study, lesbian and bisexual women actually had a 27% higher risk of type 2 diabetes than heterosexual women. Even more concerning, the risk was 144% higher for those in the 24 to 39 age group, compared to heterosexual women in this age group.

-

In a third study, gay and bisexual men were less likely to meet recommended physcial activity guidelines and bisexual men were more likely to have excess weight or obesity than heterosexual men. Additionally, lesbian and bisexual women were both more likely to have excess weight or obesity than heterosexual women.

Dr. Lauren Beach, research assistant professor of medical social sciences and preventive medicine at Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine, stressed the need for more research to understand the link between diabetes and the LGBTQ population. There is simply not enough data on the prevalence of diabetes, diabetes-related complications, and health outcomes in this population to be able to draw significant conclusions or make recommendations.

For healthcare providers, the best way to begin addressing the disparities that LGBTQ people with diabetes face is to create a welcoming environment for the people they treat.

Dr. Jamie Feldman, associate professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health at University of Minnesota, emphasized that transgender people in particular face additional and different barriers than lesbian, gay, and bisexual people.

In order to reduce barriers for these individuals, he said, we should:

-

Affirm – using people’s preferred names and pronouns, creating a gender-inclusive office space, and making sure that gender-affirming interventions are prioritized in a person’s care, even when it might interfere with diabetes-related treatments.

-

Address – by treating things like gender dysphoria, mental health, and substance use that exacerbate diabetes risk and complications, and integrating gender-affirming hormonal treatment into diabetes care.

-

Advocate – for the inclusion of gender-affirming practices and policies in health insurance forms, electronic medical records, research, and legal or civil protections.

To learn more, read:

Women with Diabetes – Benefits and Barriers to Exercise

If done safely, every person with diabetes can benefit from exercise, but there are unique advantages for women. Unfortunately, women with diabetes face barriers to exercising regularly.

Read the full coverage here.