The Best and Worst Diabetes Food Advice I've Seen

By Adam Brown

By Adam Brown

By Adam Brown

The lame food advice at my diagnosis, why it didn’t work, and my #1 Bright Spot solution

I’ll never forget the diabetes food advice I received from my doctor at diagnosis:

“You can eat whatever you want, as long as you take insulin for it.”

In my view, this advice is misleading, overly simplistic, and damaging. In fact, I’d nominate it for the “worst” diabetes food advice out there. Unfortunately, those who are newly diagnosed tell me it is still common. Ugh.

Eating “whatever I wanted” and taking insulin for it was the worst kind of blank check – it set me up for years of out-of-control high blood sugars, deep and prolonged lows, huge guesstimated insulin doses (and therefore big mistakes), mood and energy swings, and lots of diabetes frustration. My blood sugar rarely stayed in my target range (70-140 mg/dl), since the effort required was so high.

It wasn’t until I took some nutrition classes in college, shared a dorm with a bodybuilder, started writing at diaTribe, and began using a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) that I landed on the food advice below: eating fewer carbs and more fat had a game-changing impact on my diabetes, insulin dosing burden, overall health (including cholesterol), and quality of life. In Bright Spots & Landmines, this advice appears first in the book for a reason – it’s been the most important tool for improving my life with diabetes. I’ll follow up next month with an updated list of foods I currently eat, recipes, and interesting new food tricks I’ve been testing.

.png)

Eat less than 30 grams of carbohydrates at one time.

Eating fewer carbohydrates at one time is the most important Bright Spot I’ve ever discovered for tackling the hardest part of diabetes: food. I aim for less than 30 grams of carbs at one time, and from many years doing it, I’ve experienced a slew of amazing benefits:

-

Keeps my blood sugar levels in the tight range of 70-140 mg/dl for 75% of the day or more.

-

Brings a low average blood sugar level of around 120 mg/dl, equating to an A1c of around 6%.

-

Almost never causes extreme blood sugar values less than 55 mg/dl or over 200 mg/dl (just 0.7% of the time).

-

Uses 50%-80% less mealtime insulin than higher-carb meals, dramatically shrinking the risk of a dangerous insulin overdose.

-

Requires less time thinking and worrying about diabetes.

-

Eliminates lots of mood swings and mental fog, since my blood sugar levels are more predictable.

-

Brings less hunger and hypoglycemia food binges.

-

Keeps my weight, cholesterol, and blood pressure at goal.

Eating fewer carbs sounds “restrictive,” but the game-changing diabetes and quality-of-life benefits have come from filling and tasty food (see the “What I Actually Eat Section” in the book). I eat a lot of vegetables, nuts, seeds, olive oil, eggs, fish, chicken, beef, and some berries – typically about 70-120 grams of carbs per day (10%-15% of my daily calories), and most of those carbs come from fiber. The majority of my calories come from fat (60%-70%), with the rest from protein (15%-20%). This low-carb, high-fat ("LCHF") approach works far better than the lame food advice I got after diagnosis.

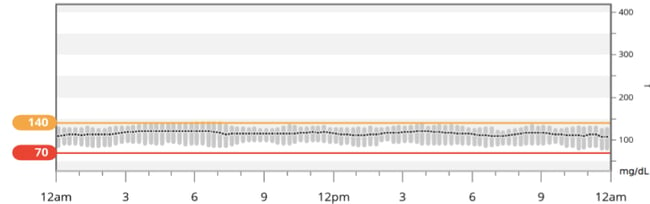

I’ve found what works for me after reading the research, trying different eating approaches, learning from others with diabetes, and looking at my own glucose data and lab results. My most recent three months of CGM data, shown below, demonstrate the Bright Spot impact of eating fewer carbs: a steady average blood sugar of around 120 mg/dl throughout the day (black line) and glucose values consistently in my goal range of 70-140 mg/dl (narrow gray bars). I’ve seen identical patterns for several years now, and while food choices are not the only factor responsible, they play a far bigger role than anything else. Plus, this eating approach requires less diabetes work!

This graph shows my data averaged over 90 days:

The blood sugar benefits of eating fewer carbohydrates are not surprising: carbs raise blood sugar far more than fat or protein, so limiting their intake has been a tremendous Bright Spot for reducing my highs and lows and cutting my insulin needs. Low-carb meals generally increase my blood sugar by a very predictable 0-40 mg/dl over a few hours, usually requiring just 0-2 units of insulin taken right when I start eating. Conversely, higher-carb meals can increase blood sugar by 100-200 mg/dl within 30 minutes, need 2-10 times more insulin than low-carb meals, and require insulin to be taken at least 20 minutes before eating.

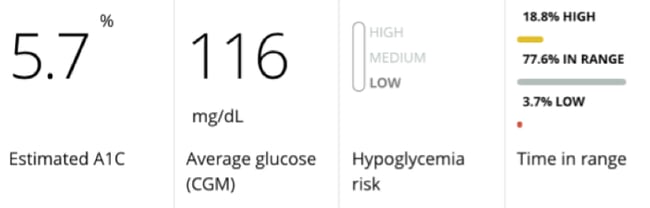

Here’s what the daily blood sugar level difference looks like, taken from my own low-carb versus high-carb experiments:

I find low-carb eating (left) is more like cruise control, giving predictable in-range blood sugars with less effort. I can put my diabetes in the background, since there is less need to carb count, less diabetes math to do, fewer swings in blood glucose, less medication to keep track of, less mental fog from highs and lows, and fewer worries.

Conversely, higher-carb eating (right) is like driving aggressively with the gas and brake, alternating between highs and lows – it’s a scarier, rollercoaster drive that requires far more attention and diabetes effort.

I’m not a believer in “diets,” which imply a short-term, exhausting sprint with a finish line. Eating is a big part of life, so it needs to be sustainable, enjoyable, and balance many factors: quality of life, diabetes hassle, glucose numbers, taste, weight, cholesterol, and more.

Eating fewer carbs is the single most important decision I’ve ever made for keeping my blood glucose in a tight range, taking insulin safely, reducing my diabetes burden and stress, and improving my quality of life and overall health.

This equation is different for every person, though many diaTribe readers with diabetes (including many parents) have written me with identical experiences. Some researchers agree too: a recent review in the journal Nutrition argued that reducing carbohydrates should be the “first approach” to managing type 2 diabetes and is “the most effective” addition to insulin in type 1 diabetes. The 26 authors reference 99 other publications to make their case.

I certainly wish I could go back in time and give myself this Bright Spot food advice at diagnosis – it would have saved me ten years of out-of-control blood sugars and diabetes frustration.

Important Notes

Eating fewer carbohydrates can reduce insulin and medication needs; use caution to avoid hypoglycemia. Now that I’m adjusted to it, I actually experience less hypoglycemia with low-carb eating; since the insulin doses are so much smaller, my mistakes are also smaller and therefore less likely to result in lows. Work with a healthcare provider to reduce your medication doses safely.

Do not take my word for this! For the next week, try different amounts of carbs per meal – e.g., 15, 30, 60, and 90 grams – and monitor the impact on blood sugar, mood, and energy levels over the next few hours. What patterns do you notice?

-

“Wait, how many grams of carbs are in _____?” Everything in the “What I Actually Eat” section in the book has less than 30 grams of carbs in one serving, and most items have less than 15 grams of carbs. The best way to learn for yourself is to look at the grams of carbohydrates on nutrition facts labels on packages, use food apps like myfitnesspal and Lose It!, websites like nutritiondata.self.com, or simply search on Google with a phrase like “Carbs in raspberries.” (In my experiments, Google answered pretty accurately, pulling data from a government database.) Pay careful attention to “serving size” – how large one portion is – since it drives the number of carbs. The beauty of choosing low-carb foods is that accurate carb counting becomes much less important.

Even eating just one low-carb meal per day can make a tremendous difference. I would choose breakfast if I only had to pick one, since it’s usually the most challenging meal of the day with diabetes: high-carb and sugary options, little prep time, more insulin resistance, and often a high blood sugar level to begin with. (See the second Bright Spot in the food chapter.)

Reduce carbs gradually and be patient – it takes at least two weeks for the body to adapt to lower-carb eating, according to researchers Drs. Jeff Volek and Stephen Phinney. Though you should see immediate blood sugar results (in my experience), it can take time for the full range of benefits discussed above. For more background, I highly recommend their book, The Art & Science of Low Carbohydrate Living.

A handful of healthcare providers and nutritionists I’ve met do not agree with this approach, arguing that not enough long-term research exists on low-carb eating. My own health data and quality of life has convinced me, without a doubt, that this is a critical Diabetes Bright Spot in the short- and long-term. Interestingly, eating more calories from fat and fewer from carbs has improved my cholesterol and triglyceride levels (lipids) and body weight, contrary to the typical advice about eating too much fat. Gary Taubes’ excellent book Good Calories, Bad Calories or the shorter Why We Get Fat and What to Do About It delves into the fascinating and complicated connection between diet and heart disease.

This article was taken from Bright Spots & Landmines: The Diabetes Guide I Wish Someone Had Handed Me, a new book by Adam Brown. The book is full of actionable advice to help you with your diabetes. Get your copy of Bright Spots & Landmines here as a free/name-your-own-price download. You can also purchase it on Amazon in paperback ($6.29) and Kindle ($1.99). The print book is priced at cost to ensure widespread access, and 100% of proceeds from digital downloads benefit The diaTribe Foundation, a 501(c)(3) non-profit.

Also, if you’ve benefitted from Bright Spots & Landmines, could you take a few minutes to write a one-sentence Amazon review sharing your experience? It would help us so much!