How Do We Prevent a Diabetes Avalanche?

.png) By Amelia Dmowska and Ava Runge

By Amelia Dmowska and Ava Runge

A major call for creativity, urgency, and new approaches to behavior change from expert panelists at SXSW 2017

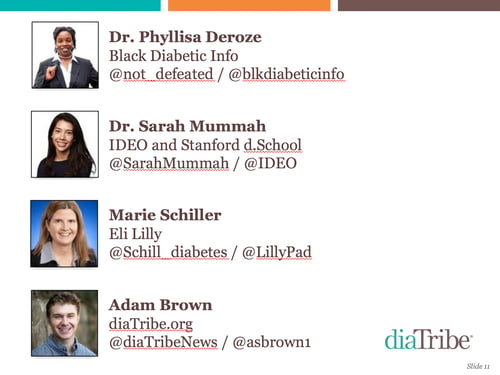

The annual 2017 South by Southwest (SXSW) conference drew tens of thousands of attendees to Austin, TX, to learn about the latest in entertainment, technology, culture, and healthcare. For the first time ever, The diaTribe Foundation produced two SXSW panels, including a session on one of the most pressing questions in healthcare: How Do We Prevent a Diabetes Avalanche? diaTribe’s very own Senior Editor Adam Brown moderated this fascinating and important conversation with Dr. Phyllisa Deroze, Founder of Black Diabetes Info; Dr. Sarah Mummah, Behavioral Scientist and Senior Designer at IDEO; and Marie Schiller, a Vice President at Eli Lilly.

Nearly 100 attendees gathered to hear the panelists’ insights on type 2 diabetes prevention and management, behavior change, education at diagnosis, and more. Below, are some of their key takeaways that focus on urgency, how to actually achieve healthy habits, what healthcare providers could do better, the importance of community, and why we should focus less on problems and more on solutions.

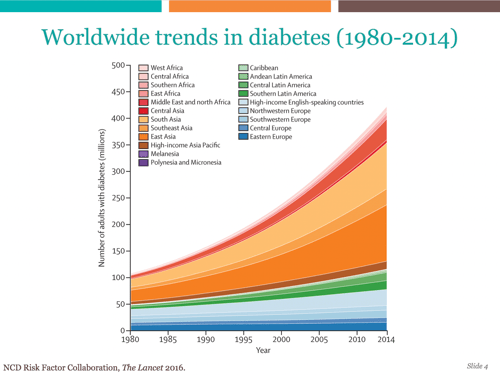

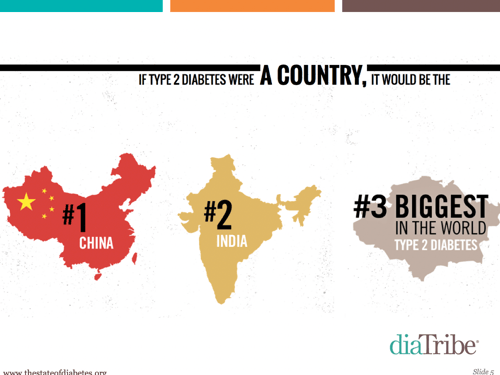

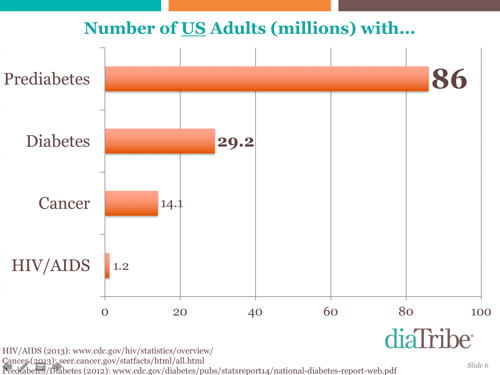

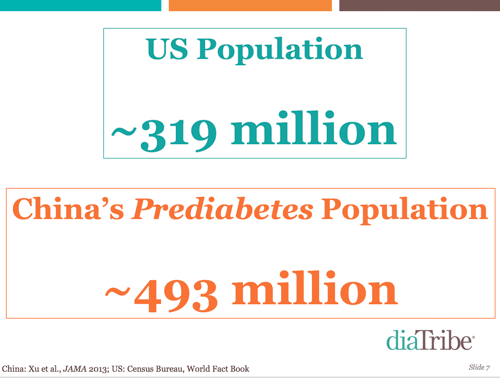

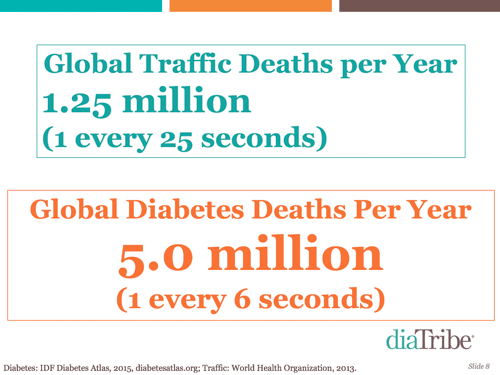

Elevating the national (and international) urgency about type 2 diabetes and prediabetes is a “must.” Adam opened the discussion with astounding stats on diabetes and prediabetes. If everyone who had type 2 diabetes were a country, it would be the world’s third largest country after India and China. Meanwhile, the estimated prediabetes population in China (about 493 million) is greater than the entire US population (319 million people). Globally, there are four times as many diabetes deaths (5 million) than traffic deaths (1.25 million) per year, a reminder that self-driving cars may have less upside than improving diabetes care. More people in the US have diabetes (29 million) and prediabetes these striking figures, Adam pointed out that despite all the attention that cancer and HIV/AIDS receive, their combined populations are half the size of the US diabetes population.

.png)

Tiny wins and small steps are essential for forming habits and changing behavior. The panelists said that drastic changes – like trying to replace every single meal with a salad – can often be daunting and ineffective. They recommended introducing small changes to established routines (e.g., eat one more vegetable per day, or exercise for just five minutes per day). These small changes can build a sense of momentum and lead to bigger changes over time. On a similar note, Dr. Mummah of IDEO said that behavior change should be countable, positively framed, and tangible. Adam said that free resources such as Dr. BJ Fogg’s Tiny Habits program can help people build habits through small, incremental steps.

- “A really drastic change may be hard to do, so you admit defeat. If you give people really big challenges, you undermine their confidence in being effective. If you can start with tiny behaviors that build, you set people up for success.” – Dr. Mummah

- “Inciting behavior change with small, incremental steps is much more effective than dumping huge behavior change asks on people. Many people get advice to make a huge change and they don’t want to hear it because it’s a huge leap, so they give up. I know – this has happened to me!” – Adam Brown

Healthcare providers need to meet their patients “where they’re at” and use more uplifting language. Dr. Deroze recounted stories of her diagnosis, where the advice she received was generic, negative, and not personal to her needs. Ms. Schiller discussed how physicians approach diabetes with a long-term perspective, which often drives ineffective scare tactics. Adam and Dr. Mummah argued for a reframe of the usual discussion around motivation and behavior change.

- “Many people hate hearing negatives because it’s hard to prioritize the long game. One of the things that we argue in diaTribe and my upcoming book (Bright Spots & Landmines) is why you should prioritize something right now. How does an in-range blood sugar make me feel today – more energy, better sleep, etc. If we gave people more action-oriented NOW messages, we could make a bigger difference.” – Adam Brown

- “Many physicians are looking forward but end up using scare tactics. It’s important to educate healthcare providers about how to communicate properly.” – Ms. Schiller

- “I went to a nutritionist many years ago, and it helped. I’ve lost 85 pounds since. But at the time, she was giving me all these ideas and I kept saying ‘no.’ Her mentor interrupted me frustrated and told me I was resistant to everything! the nutritionist wanted me to eat Raisin Bran. But I ate Fruit Loops. I had chicken thighs in the fridge, and she wanted me to eat chicken breasts. Eventually, the young nutritionist told her mentor to hold on and approached the situation differently. She made a plan with me to eat half chicken breasts and half chicken thighs. When the thighs were out, she told me not to buy them anymore. She told me to buy cereal at the store – any cereal I wanted – but it had to have at least five grams of fiber. I had to mix a little bit of it with Fruit Loops or Apple Jacks. Eventually I got to half and half, and then when those Fruit Loops were out, I didn’t buy them anymore. Her advice changed my palate. She met me where I was.”

- “The long-term outcomes aren’t going to get you out of bed. Initially, they might be motivating, but two weeks or a month in, when you’re making a decision between a donut and a salad, you probably won’t think about how it will affect your long-term diabetes risk. We have to focus on the process and make the process rewarding in and of itself.” – Dr. Mummah

- “All the information I got at diagnosis was dismal. The images were a turnoff. The data for African Americans suggested that they got more amputations and more blindness. It made it seem like I had gotten a diagnosis and that I was dying rather than that I would be a person living with diabetes. This depiction prohibited me from learning how to manage diabetes.” – Dr. Deroze

.png) It is critical to have a strong community for people with type 2 diabetes and prediabetes – both online AND offline. There are few online or offline centers for people with diabetes and prediabetes to rally together. While the Diabetes Online Community (#DOC) is a robust online presence, many people still do not have access to digital resources, and even if they do, there is significant stigma in being “out” online. All the panelists said that we need to work together to build a larger community to raise awareness, provide support, and offer resources for people with diabetes and prediabetes.

It is critical to have a strong community for people with type 2 diabetes and prediabetes – both online AND offline. There are few online or offline centers for people with diabetes and prediabetes to rally together. While the Diabetes Online Community (#DOC) is a robust online presence, many people still do not have access to digital resources, and even if they do, there is significant stigma in being “out” online. All the panelists said that we need to work together to build a larger community to raise awareness, provide support, and offer resources for people with diabetes and prediabetes.

- “If someone gave you $10 million right now, what would you invest in or test in diabetes?” Interestingly, Dr. Deroze said she would “definitely” go offline – it was an in-person support group shortly after diagnosis that really changed her life with diabetes. She added: “There’s a digital divide that still exists – many in the community don’t have access to the DOC. Annually, I have workshops at a local library and I bring education that I’m getting from the DOC to my town community. For example, we have a “learn the plate” method day. We have a buffet, and they fix their plate with ox tails, chicken wings, collard greens, corn bread – whatever they normally do. Then I teach them how they should do it.”

- “There is no foundation for people with prediabetes; no one has championed that cause. Ninety percent of people who have prediabetes don’t know. We need to create awareness and collaboration.” – Ms. Schiller

In diabetes and prediabetes, we need less problem-focused research (what’s going wrong and why) and more solution-oriented research (what works and why). Dr. Mummah put it well: “From my perspective, we don’t necessarily need more data. We need to be testing solutions. There is a subtle distinction between problem- and solution-oriented research. In problem-oriented research, you ask questions like “Are children who live in communities with fewer parks and green spaces less physically active?” In solution-oriented research, instead, you ask “Does adding green parks increase physical activity or does limiting advertising to children on TV reduce obesity?” If you look at neighborhood safety, it makes sense that you would be less physically active if you feel unsafe. You’re less likely to go outside your home if you’re likely to be mugged or putting yourself in danger. A solution-oriented approach to this problem would say, “Let’s increase street lighting, let’s hold a music festival one evening every month to bring people outdoors in the evening. Let’s create a neighborhood watch program.” Then if the experiment works, you have a solution that’s ready to implement and scale. It’s a subtle shift, but it’s powerful.”