Sports and Exercise: The Ultimate Challenge in Blood Sugar Control

Sometimes, it amazes me how smart the pancreas really is. It always seems to know what to do to keep blood sugars in range, even under the most challenging circumstances. Having an argument with your partner? It churns out some extra insulin to offset the “fight or flight” response (make that flight only, if you’re smart). Upset stomach keeping you from eating the way you normally eat? Insulin secretion drops off a bit. Can’t resist the aroma of a fresh bagel (something that, in my opinion, was forged by the Diabetes Devil himself)? Pancreas cranks out just enough to cover it.

Participation in sports and exercise presents a special challenge. That’s because physical activity can affect blood sugar in multiple ways. With increased activity, muscle cells become much more sensitive to insulin. This enhanced insulin sensitivity may continue for many hours after the exercise is over, depending on the extent of the activity. The more intense and prolonged the activity, the longer and greater the enhancement in insulin sensitivity. With enhanced insulin sensitivity, insulin exerts a greater force than usual. A unit that usually covers 10 grams of carbohydrate might cover 15 or 20. A unit that normally lowers the blood sugar by 50 mg/dl might lower it by 75.

Some forms of physical activity, most notably high-intensity/short duration exercises and competitive sports, can produce a sharp rise in blood sugar levels followed by a delayed drop. This is due primarily to the stress hormone production or “adrenaline rush” that accompanies these kinds of activities.

Let’s take a look at these two different situations in greater detail.

aerobic activities

Most daily activities and aerobic exercises (activities performed at a challenging but sub-maximal level over a period of 20 minutes or more) will promote a blood sugar drop due to enhanced insulin sensitivity and accelerated glucose consumption by muscle cells. To prevent low blood sugar, one can reduce insulin, increase carbohydrate intake, or a do combination of both.

When exercise is going to be performed within an hour or two after a meal, the best approach is usually to reduce the mealtime insulin. If you exercise at a time when rapid-acting insulin is not particularly active, such as upon waking, before meals or midway between meals, it is best to consume extra carbohydrate prior to the activity. For activities lasting more than two hours, it can also be helpful to reduce long-acting or basal insulin.

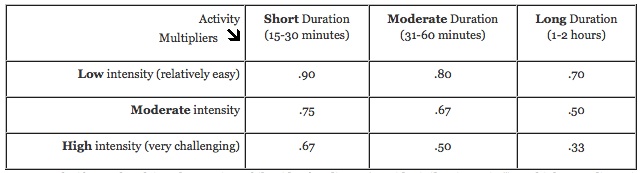

When adjusting mealtime insulin, both the dose to cover food and the dose to cover a high reading are made more effective by exercise and need to be reduced. To accomplish this, try using an activity “multiplier.” This means that you calculate your mealtime insulin as usual (based on the food and the blood sugar level), and then multiply the dose by a factor that reduces the dose by a certain percentage:

For example, if you take a leisurely 20-minute bike ride after dinner (consider it “low intensity”), multiply your dinner insulin dose by .90, which reduces the dose by 10%. If you plan a much more intense 90-minute ride up and down hills (consider it “high intensity”), multiply your dinner dose by .50. This reduces the dose by 50%.

Not only do activity multipliers help you to avoid hypoglycemia, they also enable you to lose weight more effectively. Reducing insulin means that your body will store less fat and break more down for use as energy.

If you take medication other than insulin for your diabetes, you may or may not need to reduce or eliminate the dose. Only certain medications can cause hypoglycemia; medications that do not have the potential to cause hypoglycemia should not be changed.

If you take a medication that can cause hypoglycemia, continue to take it prior to your first couple of exercise sessions and see what happens. But check your blood sugar often and be prepared with rapid-acting carbs in case you drop. If your blood sugar drops below 70 mg/dl (4 mmol/l) during or after exercise, reducing or eliminating the medication might be in your best interest. Check with your doctor before making this type of change on your own. Pramlintide (Symlin) and Byetta/Victoza should not cause hypoglycemia by themselves. However, when taken along with rapid-acting insulin prior to exercise, they can lead to severe hypoglycemia that may be very difficult to treat - it is generally not a good idea to take either with insulin right before exercising.

when snacks are needed

Under certain conditions, extra food intake will be necessary to prevent hypoglycemia during exercise. For example, when exercise is going to be performed before or between meals, reducing the insulin at the previous meal would only serve to drive the pre-workout blood sugar very high. A better approach would be to take the normal insulin dose at the previous meal and then snack prior to exercising. If you decide to exercise soon after you have already taken your usual insulin/medication, snacking will be your only option for preventing hypoglycemia. Also, during very long-duration endurance activities, hourly snacks may be necessary in addition to reducing insulin/medication.

The best types of carbohydrates for preventing hypoglycemia during exercise are ones that digest quickly and easily, better known as “high glycemic-index” foods (for a review of the glycemic index, see Learning Curve from diaTribe #14). These include sugared beverages (including juices, soft drinks and sports drinks), breads, crackers, cereal, and low-fat (i.e., non-chocolate) candy.

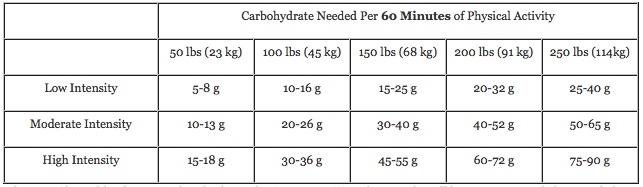

The size of the snack depends on the duration and intensity of your workout. The harder and longer your muscles are working, the more carbohydrate you will need in order to maintain your blood sugar level. The amount is also based on your body size: the bigger you are, the more fuel you will burn while exercising, and the more carbohydrate you will need.

Granted, there is no way of knowing exactly how much you will need, but the chart below should serve as a reasonable starting point. To use the chart, match up your approximate body weight to the general intensity of the exercise. The grams of carbohydrate represent the amount that you will need prior to each hour of activity. If you will be exercising for half an hour, take half the amount indicated. If you will be exercising for two hours, take the full amount at the beginning of each hour.

Of course, if your blood sugar is already elevated prior to exercising, fewer carbs will be necessary. And if you are below target, additional carbs are needed.

The best way to determine the optimal size and frequency of your workout snacks is to test your blood sugar before and after the activity. If it holds steady, you have found the magic number of carbs. If it rises significantly, cut back on the number of carbs. If it drops significantly, take more carbs or eat more frequently next time.

anaerobic activities

Anaerobic exercises are high-intensity and often are performed in short “bursts” – such as weight lifting.

It is not unusual to experience a blood sugar rise at the onset of high-intensity exercise. This is caused by a surge of stress hormones that oppose insulin’s action and cause the liver to dump extra sugar into the bloodstream. Exercises that often produce a short-term blood sugar rise include:

- Weight lifting (particularly when using high weight and low reps)

- Sports that involve intermittent “bursts” of activity like baseball or golf

- Sprints in events such as running, swimming and rowing

- Events where performance is being judged, such as gymnastics or figure skating

- Sports activities in which winning is the primary objective

preventing the highs

Nobody likes to have high blood sugar when striving for peak performance. But if you can predict it, you can prevent it. Remember at the beginning of this article when we were praising our pancreas for its ability to manage blood sugar even in the face of an adrenaline rush? Well, you need to think like a pancreas and take extra insulin. (Think Like A Pancreas… wouldn’t that make a nice book title?)

To determine how much extra insulin to take before a high-adrenaline-type event, consider how much your blood sugar normally rises. If it goes up 200 mg/dl and your sensitivity factor is 50 mg/dl per unit (you drop 50 points per unit of insulin), you would normally need to give four units to prevent the rise. DO THIS AND YOU MIGHT PASS OUT. Remember, physical activity makes your insulin more potent! Give yourself half the normal amount. And give it about half an hour beforehand so that it will keep you from being too high when the activity begins.

The same “half-the-usual-dose” rule applies to high blood sugars immediately before or immediately after competitive/high-intensity events. Take half the usual “correction insulin” for high blood sugars in these situations.

If you are nervous about giving insulin before exercise, check your blood sugar more often than usual (perhaps every half hour or so), and have glucose tablets or some other form of fast-acting carbohydrate nearby. Or better yet, start using a continuous glucose monitor to track your blood sugar minute-to-minute. With some experience, you will develop greater confidence and have the ability to fine-tune your correction doses.

delayed effects

Ever finish a workout with a terrific blood sugar only to go low several hours later or overnight? Many aerobic activities (particularly those that are long or intense) and most anaerobic exercises cause blood sugars to drop several hours later. This phenomenon even has its own name: Delayed Onset Hypoglycemia. There are two reasons why this takes place: prolonged, enhanced sensitivity to insulin, and the need for muscle cells to replenish their own energy stores (called glycogen) following exhaustive exercise.

If you take injections, you can counter delayed-onset hypoglycemia by having a low-glycemic-index snack before bedtime – such as peanut butter.

Delayed-onset hypoglycemia is unique to each individual. But again, if you can predict it, you can prevent it. The best way to deal with it is to first keep records of your workouts so that you can learn when it happens (After what types of activities? How many hours later?), and then make adjustments to prevent it. For example, if you tend to drop low at 3 a.m. following long evening practices, try lowering your pump’s basal insulin by 30-40% for eight hours following those practices. If you take injections, you can lower your long-acting insulin by 20-25% or have a low-glycemic-index snack before bedtime, without insulin coverage. Examples include nuts, milk, yogurt, peanut butter, or chocolate. (Finally! A therapeutic application for chocolate.)

Some people also find that their blood sugar rises after they finish exercising. This is often due to the delayed digestion of food that was consumed prior to the workout, or the effects of disconnecting from a pump or having injected mealtime insulin absorb too quickly. Whatever the cause, a dose of rapid-acting insulin right after the workout will usually remedy the situation.

think before you stink

Exercise and other physical activities are meant to be enjoyed. Managing your blood sugars effectively before, during, and after physical activity will ensure that you feel good, stay safe and perform your best. It’s worth a few moments to plan out your blood sugar management strategies before exercise, because nothing will screw up a good workout like a high or a low. And if you would like some expert coaching in this area, drop me a line! There is nothing I like more than helping athletes (at all levels) to succeed.

Except maybe a fresh bagel.

Editor’s note: Gary Scheiner MS, CDE is Owner and Clinical Director of Integrated Diabetes Services, a private consulting practice located near Philadelphia for people with diabetes who utilize intensive insulin therapy. He is the author of several books, including Think Like A Pancreas: A Practical Guide to Managing Diabetes With Insulin. He and his team of Certified Diabetes Educators work with people throughout the world via phone and the internet. An exercise physiologist by trade, Gary has had type 1 diabetes for 25 years and serves on the Board of Directors for the Diabetes Exercise & Sports Association. He can be reached at gary@integrateddiabetes.com, or toll-free at 877-735-3648.